The Meaning of Christmas Depicted in 10 Glorious Works of Art

1. “Nativity” by Giotto (1303-05)

Considered the first in a line of great artists who contributed to the Renaissance, Giotto di Bondone, referred to simply as Giotto, was an Italian painter and architect from Florence in the late Middle Ages. His “Nativity” is part of a fresco cycle dedicated to the life of the Virgin Mary. Here, Giotto changes the story of the Nativity slightly by adding an ox and a donkey. The ox is a symbol of the New Testament while the donkey symbolizes the Old. Together they show us the contrast between those who see and know and those who are blind to the new light that came with the birth of Jesus Christ. The faces and body language in the scene display strong human emotion. Mary casts a long, sad look at Jesus. Her sadness projects the future when she will see her son on the cross. With this painting, Giotto shows us the Nativity in an entirely new way. It’s filled with intense human drama. The mother and the baby are making eye contact. We see their strong connection. As Giotto moves away from the Byzantine style that had proceeded this time period, we see figures that are warm and approachable. This was truly something new for its time.

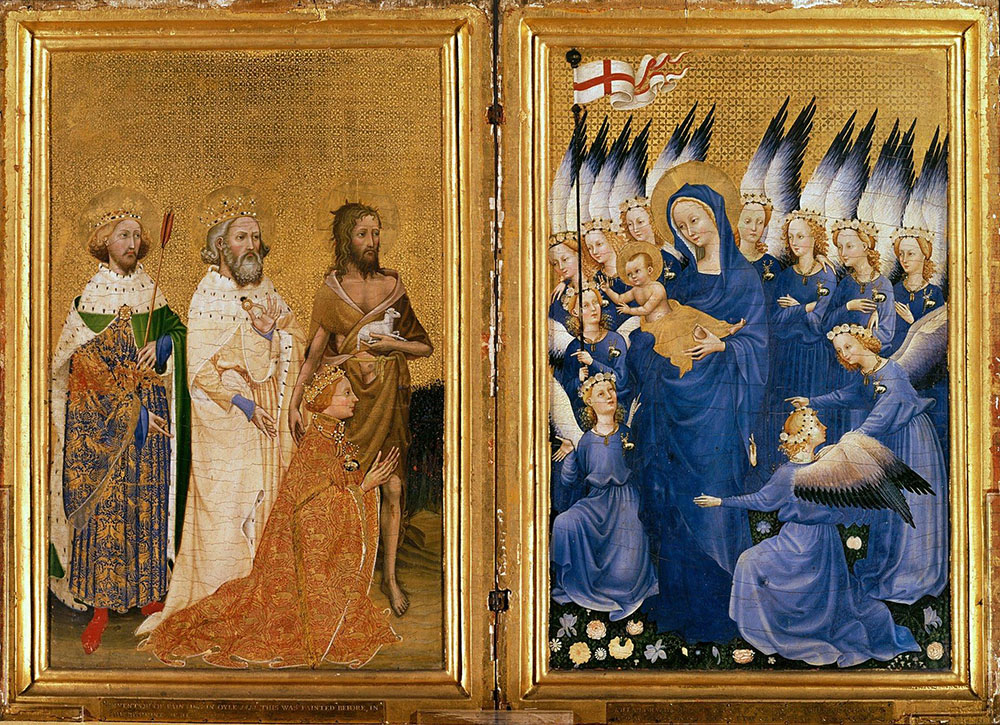

2. “The Wilton Diptych” unknown artist (c 1395-99)

“The Wilton Diptych,” an outstanding example of the International Gothic style, was painted for King Richard II of England (seen kneeling before Mary and the Infant Jesus). This is an extremely rare piece to have survived since late Medieval times. King Richard II is presented to Mary and Jesus by his patron saint, John the Baptist, as well as by the English royal saints Edward the Confessor and Edmund the Martyr. The scene makes reference to the feast of Epiphany (January 6th) when Christ was adored by three kings. This is also the day the feast of the Baptism of Christ by John the Baptist was celebrated. The figure of John appears carrying a lamb (a reference to the shepherds who visited after the birth of Christ) wearing his usual hermit’s dress. The white pennant bears the cross of St.George as a symbol of Richard’s kingship and of the entire Kingdom of England. It is believed Shakespeare viewed this painting and was influenced by the way the angels are presented in this diptych 200 years later when he wrote the lines for Act III, Scene 2 of Richard II:

The breath of worldly men cannot depose

The deputy elected by the Lord:

For every man that Bolingbroke hath press’d

To lift shrewd steel against our golden crown,

God for his Richard hath in heavenly pay

A glorious angel: then, if angels fight,

Weak men must fall, for heaven still guards the right.

3. “The Annunciation” by Fra Angelico (1438-45)

“The Annunciation” is an Early Renaissance fresco by Fra Angelico. This version of the Annunciation is important in that it transitions away from a typical Gothic Annunciation painting which contained the archangel Gabriel visiting Mary indoors, with Mary enthroned. In this version, Gabriel visits Mary in an indoor setting. Angelico is credited as the inventor of this new type of composition. He’s made a work of art that shows us the transition out of the Gothic period and into the Renaissance in the way he handles space and lighting. He’s an artist who is known by art historians as “a rare and perfect talent”. In “The Annunciation,” we see why.

4. “Nativity at Night” by Geertgen tot Sint Jans (c 1490)

Geertgen tot Sint Jans (meaning ‘little Gerard of Saint John’) was an Early Netherlandish painter who died at the young age of 28. Not much is known about him, yet he gave us one of the most beautiful interpretations of the birth of Jesus in his “Nativity at Night.” It has been called “one of the most engaging and convincing early treatments of the Nativity as a night scene”.

A brilliant light in the foreground comes from Jesus as he lay in the crib, illuminating his mother, Mary. As she bends forward with her hands in prayer, we see Joseph standing in the background. We see a second contrast between dark and light as the angel announces the birth of Jesus to the shepherds. The shepherd’s fire gives us a third and lesser light source.

In the 14th-century, St. Bridget of Sweden wrote of the idea of the infant illuminating the Nativity scene. She wrote that the light of the child was so bright ‘that the sun was not comparable to it’. A century later, Geertgen creates this idea by using extreme contrasts of light and dark to heighten the sense of the miraculous birth of Jesus.

5. “Mystic Nativity” by Sandro Botticelli (1500)

“Mystic Nativity” is the only signed work from Italian Renaissance master Sandro Botticelli. Botticelli shows Mary and Jesus as larger than others as well as their surroundings which is a practice of the medieval style of representing figures. We see a scene of joy and celebration, yet we also see dark premonitions. Jesus lays on a shroud which is representative of the one He will be wrapped in after His death. There are angels at both the top and the bottom of the scene. Heaven appears at the top as a great golden dome. Angels on the bottom are consoling three men, lifting them up from the ground, as seven devils descend into the darkness of the Underworld. In Renaissance times, paintings depicting the Last Judgment showed both the damned and the saved on the day of reckoning at Christ’s Second Coming. In “Mystic Nativity,” Botticelli is telling us not only to recognize the birth of Jesus, but look ahead to the moment when He will return.

6. “The Sistine Madonna” by Raphael (1512-13)

This painting by the Italian High Renaissance artist Raphael was commissioned by Pope Julius II in honor of his late uncle, Pope Sixtus IV, and simply required that the Virgin and the Infant Jesus should be in the company of St. Sixtus and St. Barbara. The Infant Jesus and Mary appear surrounded by a brightness so intense that the saints can hardly bear it. Mary stands on the clouds to revel Jesus to the world as its Redeemer. St. Barbara is gazing down toward the earth, making sure we are aware the Jesus Christ is being presented to us. This is a most impressive work of art. Some have claimed to have reached a state of religious ecstasy (an increase in spiritual awareness accompanied by visions and emotional euphoria) at the mere sight of the canvas. This piece includes the famous “Raphael’s cherubs.” They appear at the bottom of the painting. The winged angels have been heavily marketed over the past few decades in postage stamps, on postcards, on clothing, and many other ways. So, why did Raphael include cherubs in this work of art? According to some art historians, it’s believed that children would come to watch Raphael as he painted the Madonna. Raphael, being struck by the way they gazed wistfully as he worked, captured to perfection their expressions and placed them on the faces of the most famous cherubs in history.

7. “The Hunters in the Snow” by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1565)

This painting by Flemish artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder is considered one of the greatest paintings of all time, and is said to be the world’s most popular classical Christmas card design. It is one in a series of paintings in the medieval and early Renaissance tradition of depicting different times of the year which showed various rural activities/work to represent different months of the year. We see hunters returning from an unsuccessful expedition. Visually we have a sense of a cold, calm wintry day. Colors are muted and trees are bare. Looking past the hunters, we see an array of busy people: adults preparing food at an inn, as well as silhouetted figures ice skating and playing hockey. The 1560s was a time of religious revolution in the Netherlands, so art historians believe the meaning of “Hunters in the Snow” is simply that man himself is a powerless entity and at the mercy of the natural seasons and rhythms of the year. It implies only faith in God can bring us meaning and comfort. Like much of Netherlandish art of the 16th and 17th century, this is a low-key example of religious art, providing a very ordinary setting for its powerful message.

8. “Adoration of the Shepherds” by Caravaggio (1609)

Italian artist Michelangelo Merisi (aka Caravaggio) completed “Adoration of the Shepherds” just one year prior to his death. In this version of the biblical story, Caravaggio has abandoned the Renaissance method of highly decorative backgrounds. We’re left with an isolated view of the figures themselves against a dark, vast background. Caravaggio was known for showing brutal realism, and some critics have even described his method for creating biblical scenes as “vulgar.” He’s stepped away from the traditional methods used up to this point. As a painter of the Baroque style, he shows us divine figures represented as ordinary people. There is no holy light source. Instead, the scene is rather dark with only one central light source to illuminate all of the figures. He’s moved away from the Renaissance way of showing ornate halos on Jesus and Mary. Instead, halos are very light, barely noticeable. In this piece, Caravaggio has beautifully used the technique that he’s well-known for called chiaroscuro. Chiaroscuro is the contrast between dark and light. With this method, viewers are forced to focus on the figures, not the overall environment. He brings us a scene as if it was taken by a camera at the moment of Jesus’ birth. No posed figures. No holy light coming from the newborn. No flat expressions. No staged stable scene. The area is lit by a single candle. His style leaves us with a sense that we’ve just walked in on this moment in time.

9. “The Adoration of the Shepherds” by Guido Reni (c 1640)

Guido Reni was an Italian painter of high-Baroque style. In his “The Adoration of the Shepherds,” he shows us the scene when shepherds arrive soon after the birth of Jesus. This is based on the account in Luke’s Gospel which describes an angel appearing to a group of shepherds, telling them that Christ had been born in Bethlehem. A crowd ofangels followed saying “Glory to God in the highest, peace on earth to men of good will”. Stylistically, Reni has taken a high viewpoint in which angels balance the composition, while also reflecting the light coming from the newborn. A few well-known Christmas carols that make reference to this story include “O Come All Ye Faithful”, “Silent Night”, and “What Child Is This?”

10. “Winter Landscape” by Caspar David Friedrich (1811)

Considered the most important German artist of his generation, Caspar David Friedrich was a 19th-century German Romantic landscape painter. In “Winter Landscape,” Friedrich combines a landscape motif with religious symbolism, a common style seen in many of his works. This painting represents the hope for salvation through the Christian faith. We see a crippled man in the foreground who has abandoned his crutches. He rests against a rock before a crucifix with his hands raised in prayer. He has arrived at his destination. The man feels hope at the sight of Jesus on the cross. The hope of the resurrection. The Gothic church in the background mimics the shape of the trees in the foreground. As it emerges from the mist and rises from the ground, it symbolizes the promise of life after death.